Déjà Code

Quantifying Claude Code's duplication habit & ogling Gas Town from afar

There’s a new fashion to brag about not reading the code spat out by an AI, and I’m not talking about the many legitimate vibe coding use cases but about serious engineers doing quote-unquote serious work that they release to the wider public.

In the frontier lands of this Wild West of vibe coders lies Gas Town, Steve Yegge’s memetic shot at defining a new category of software, an orchestrator for multiple Claude Code agents coordinating on larger tasks. It’s designed to enable a sort of vibe coding on steroids. By Steve’s own admission/brag he’s never read the code of Gas Town proper:

I’ve never seen the code, and I never care to, which might give you pause. ‘Course, I’ve never looked at Beads either, and it’s 225k lines of Go code that tens of thousands of people are using every day. I just created it in October. If that makes you uncomfortable, get out now.

I’m setting up camp outside of Gas Town for now, even if I think it’s a valid exercise in AI futurism (or possibly an elaborate piece of performance art—you never know with Steve!). I’m uncomfortable setting foot in town because I’m confronted with the limitations of current frontier models every day, which makes me doubt that these kinds of entirely vibe coded mega-projects are sustainable.

I now have a decent amount of experience with a non-trivial AI-native codebase, that of GitGuessr, a game I’ve been working on on and off for a month. GitGuessr is AI-native in the sense that none of its code is handcrafted; all code is written by prompting Claude Code (Opus 4.5, and very recently Opus 4.6). But in other ways it is built in a traditional manner. I review all code, I pay attention to test coverage, and I commit changes in self-contained small chunks. I’m essentially doing trunk-based development, meaning that any one commit is fit to be deployed to production.

Even while conservatively keeping a human in the loop, this is a shockingly productive workflow. I believe it speeds up development by a factor of about 5—that is, for me personally as an experienced solo developer working on a medium-size project. I can write an amount of production-quality software in one day that in the pre-AI era would have taken me a whole work week1.

As much as I fully rely on Claude, I have to stress that I often reprompt it to substantially change code that I don’t like or that it got wrong. By far the most common reason for my follow-up prompts: Claude does a really poor job reusing existing library code and extracting new reusable code. It regularly “forgets” about library code it wrote elsewhere a while ago, and it misses opportunities to create good abstractions that span multiple files.

I assumed this was a consequence of Claude’s limited context window (200K tokens) forcing it to make hard tradeoffs about what source files to load at any given time. But when I asked Claude, it gave a simpler explanation:

The context window isn’t really the main bottleneck. Even with infinite context, I’d still need to decide to look for existing abstractions. The real issue is behavioral: I’m biased toward writing new code to solve the immediate request rather than first auditing what already exists. A human developer with the same 200K token window but the habit of checking for existing utilities would do better.

I appreciate the candor but this is not reassuring! All of this leaves me with a nagging sense that my codebase would balloon out of control if I didn’t constantly intervene with the superior human context window that is my memory. This is why I question the sustainability of Gas Town’s unsupervised approach to production software in the long run.

Quantifying Claude’s code duplication

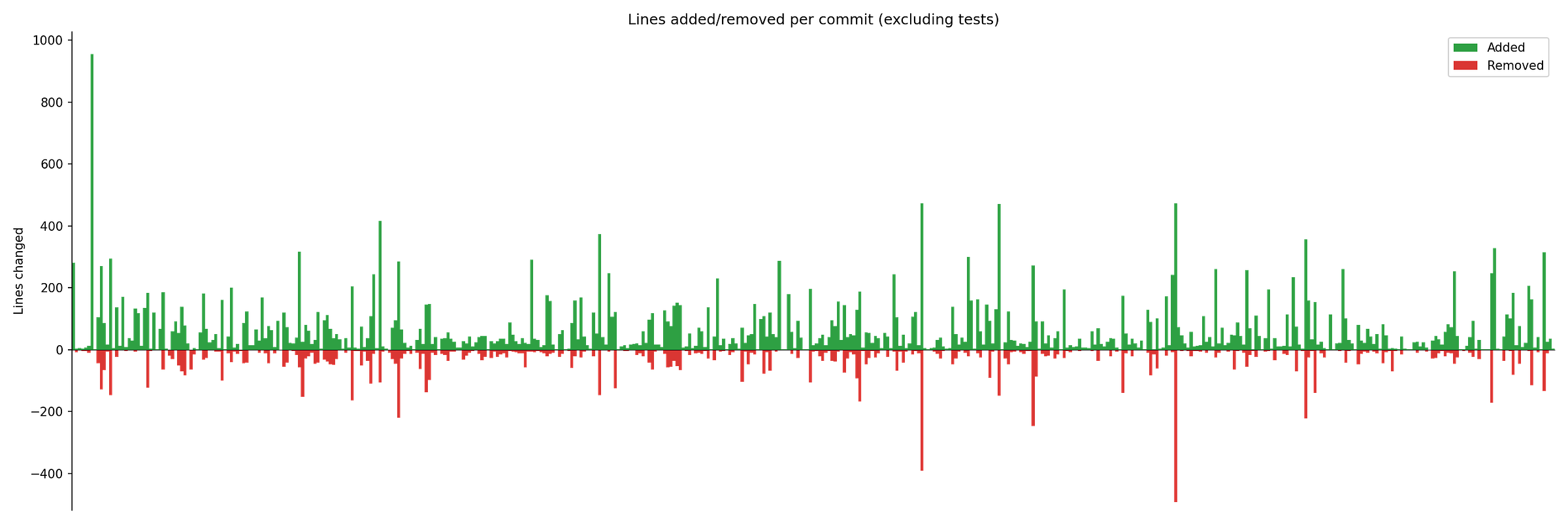

I wanted to quantify my nagging sense, using GitGuessr as a convenient real-world case study. The codebase is currently ~20K lines of TypeScript (excluding tests), accumulated over ~500 commits. Here I plotted lines of code added and removed per commit:

This is just to show that progress was pretty uniform over time. There were no massive spikes in either code added or removed—as you would expect from trunk-based development that values small-ish self-contained changes.

To measure opportunities for deduplication that Claude missed I came up with a possibly counterintuitive method: I looked at commits that reduced duplication. Given the observation that Claude pretty much never suggests code-reducing refactorings without explicit prompting, such commits almost certainly represent deduplication that only happened because of my all-too-human intervention.

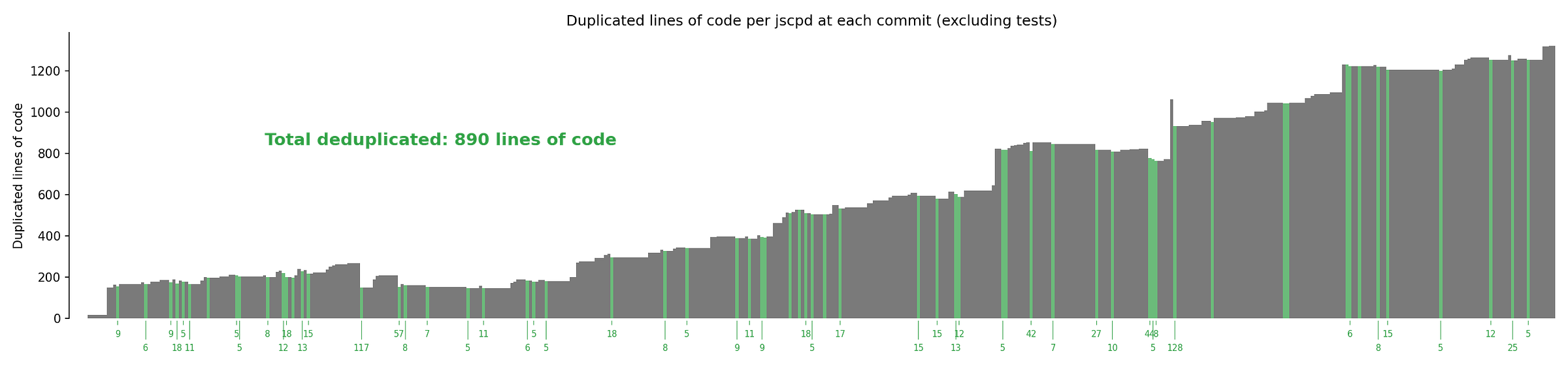

This plot shows the number of duplicated lines across the whole codebase at every commit (as per jscpd2), with deduplicating commits highlighted in green:

The total number of deduplicated lines is 890, representing ~4.5% of the codebase. In other words, if I had blindly accepted Claude’s output, the codebase would contain at least 4.5% more code that is duplicated and redundant. This is very much a lower boundary for the amount of duplicated code because I frequently prompt Claude to refactor new code before committing any part of it, which then obviously isn’t captured by this analysis.

Anecdotally these commits are indeed refactorings sprung from my own sound mind. Here are the messages from the top 10 deduplicating commits (number of deduplicated lines in parentheses):

Extract shared layout between terms and privacy policy (128 lines)

Move breadcrumb (117 lines)

Make sticky preview persistent when browsing non-target files (57 lines)

Abstract code map ownership verification for queries & mutations (44 lines)

Extract a bit more reusable code between location tables (42 lines)

Render location import errors persistently in table (27 lines)

Claim games played as anon (25 lines)

Extract some common code for game config (18 lines)

Design terms page (18 lines)

Unify ready screen and round end screen better (18 lines)

The keywords “extract”, “abstract”, “unify” clearly reveal the intent of some of these changes. According to a full textual analysis of commit messages by Claude, the commits that explicitly describe a code-reducing refactoring make up 53% of all lines deduplicated. Browsing some other commits it’s pretty clear that these do contain intentional refactorings as well.

Before everybody goes all peer review on my shoddy paper, I am aware of some methodological weaknesses here:

Not all duplication is bad. Acknowledged, though I tend to fall on the DRY side of the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) vs WET (Write Everything Twice) debate. Note to some degree I mitigated this issue by excluding trivial duplications in jscpd (those with less than 25 tokens or 5 lines of code).

Lines deduplicated in one commit may have been removed in a subsequent commit. So the lines of code deduplicated from individual commits do not necessarily add up to the true number of counterfactual duplicated code at the last commit.

Will code duplication matter?

Why care about code duplication, especially if you’re a denizen of Gas Town and reading code is beneath you anyway?

Duplication in code is a useful proxy for the lack of good abstractions in that code, which is what I really care about. Funny thing is, AIs benefit from good abstractions and modular code just as much as humans. Abstractions convey meaning and give crucial hints about how new code should be structured. If Claude manages to load the right abstractions relevant to a task into its context it will generate less code, better code.

Otherwise, if some core logic is not abstracted well and duplicated in ever more places, the risk increases that one of those places will be missed by Claude when that logic needs updating. That’s a classic setup for bugs which leaves Gas Town prone to nasty locust plagues.

So my human vigilance cut an extra 4.5% of redundant code (which, reminder, is a lower boundary). Doesn’t sound like much, but the downside compounds over time as Claude needs to deal with a larger codebase every single time, from scratch, when its context window resets. This creates some perverse incentives for Anthropic, by the way, because they make more revenue the larger the codebase and the more tokens churned. I’m afraid these incentives might mean unsupervised coding models will continue to favor verbosity over consolidation of code.

Arguably, it’s only become viable to go AI-native for production software just 3 months ago with the release of milestone models in November 2025 (Claude Opus 4.5 and GPT-5.1-Codex). These tools are so new and progress has been so rapid that my petty worries about duplicating code may very well be obsolete soon, and then I can finally strut the streets of Gas Town!

I see three complementary ways in which this might happen:

Context windows grow significantly larger, and/or tokens get significantly cheaper. Either way, it becomes possible to keep a whole codebase or large chunks of it in context at all times, in which case code duplication just isn’t that big a deal (🪦 RIP DRY). There may be an uncanny parallel to when programming moved from assembly to compiled high-level languages. Any C compiler certainly generates a lot of “duplicated” machine code that in theory could be optimised by an expert assembly programmer. But we rarely care now because the enormous benefits of high-level representation in C (or Go or Rust) override any concerns about micro-optimisation or about the size of binaries, valid concerns only when machines had radically less storage, memory and compute in the 60s. If a model can distill its own high-level representation of a codebase from holding it in context in full, we similarly may not care about the particulars of the (high-level) code anymore. The model could then even run compiler-like optimisation passes to reduce duplication. Heady stuff.

Models get better at pulling in the necessary context ad hoc to find relevant libraries and refactor code as they go. By Claude’s own admission it is biased against “first auditing what already exists”. Just letting users dial back that bias may be a good start. I also think that models are bumping up against the limitations of source code in files. Constantly scanning files feels sooo last year. It seems obvious that models would benefit from a better representation of source code, one that, e.g., indexes commonly imported public functions within a codebase to make their discovery less token-intense and less dependent on heuristics. Notice how this converges at some point with the infinite context vision from the first point.

Refactoring tools get more integrated with AI-native codebases. This is probably already happening since developer tooling is such a crowded space, and it even seems trivial to put together your own little toolchain. For example, as part of CI you could run the duplication detection tool jscpd, highlight any new duplicated code and then kick off a cloud agent to propose a refactoring to eliminate it. I’m tempted to give this a go myself to see how useful it is.

I’ve focused on code duplication in AI-native production codebases here but I’ve encountered at least two other problems that are real threats to Gas Town. One is that Claude often fails to anticipate scale. E.g., it tends to implement data aggregations in memory that at scale clearly need to happen in some data store.

And last but certainly not least, the security implications of releasing reams of unreviewed code into the wild are serious and scary. I like Johann Rehberger’s framing in The Normalization of Deviance in AI: Right now we are all gradually relaxing our standards because the AI equivalent of a “Challenger event”, a catastrophic event like the explosion of the Challenger space shuttle, hasn’t happened yet to reveal our false sense of security for what it is. We’re currently hurtling towards AI security’s Challenger event which will reset our standards and sober up those high on the fumes of Gas Town.

This brings me around to one of my core beliefs about software engineering: Creating software for yourself to run on your own machine (aka prototyping) has always been easy and is now exceptionally easy in the era of vibe coding; what’s hard is doing it for real users with real data, in a team, over a long period of time3. That kind of production-grade software cannot ignore proper abstractions, scaling and security. For now, my junior team mate Claude still heavily leans on my human expertise on these three matters to pass as a competent software engineer.

Subscribe above to receive updates on our small team of two and our explorations of AI-native development, roughly every other week. And get better at judging your favorite coding model’s output by playing GitGuessr which has launched publicly last week.

—Nik

It’s important to qualify this statement: I’m making no claims about teams working on much larger codebases. I suspect the gains from AI are harder to realise there for now but I’m currently lacking hands-on experience in such a setting.

jscpd run with arguments “--min-tokens 25 --min-lines 5”, so trivial bits of duplication are excluded.

Just as I was writing this, Kellan Elliott-McCrea, who is one of my CTO idols, published related thoughts: Code has always been the easy part