Vibe Composing

Chatting simple tunes and beats into existence. Claude takes the reins. Teaching music to Claude? An AI agent's conflict of interest.

Welcome to Next Generation Of, issue #2! Every two weeks I prototype some new piece of software, serving as a fresh case study of what’s possible today with rapidly evolving AI coding tools.

In this issue: Vibaldi, a chat interface to make music. The impatient can just check it out—but please read on for commentary.

Stuck on Strudel

Every once in a while the YouTube algorithm will offer up something that serves a niche interest I didn’t even know I had. I can’t say what I expected from a video titled “2 Minute Deep Acid in Strudel (from scratch)”—a word salad out of context if there ever was one—but when I started watching I quickly realised this would send me down a rather deep and bendy rabbit hole.

In the video, the musician and coder Switch Angel composes a track in real time within Strudel, a live coding environment for music production. It hooked me in multiple ways: the unexpected expressivity of a cryptic series of numbers and letters, the concept (then new to me) of even making music through code, her mesmerising narration of the process, her skill at shaping it all so effortlessly into a throbbing Deep Acid soundscape.

This was my first exposure to Strudel, and I subsequently played around with it. I learned that it’s open source software written in JavaScript and that, to my surprise, it runs entirely in the browser. (So what’s your excuse for building something not as a web app these days?) Seeds were planted in my mind, as the opportunities occurred to me that this opens up.

In Switch Angel’s comments many are remarking how her live narration doubles as lyrics to the track, with its quasi-dadaist poetic quality (“let’s duck it / let’s make it pump / —increase that duck attack”). But in a way she’s just plainly verbalising her musical or timbral ideas. Her highly trained skill as a musician is translating those ideas straight onto the instrument that is Strudel code.

It struck me that this process at least superficially reduces the music making pipeline to just language and code, two core domains of expertise for LLMs. With the support of AI, can we take somebody’s Switch Angel-style incantations and turn them directly into music?

I investigated and bundled some of what I found as Vibaldi1, a chat interface to make music by way of Strudel.

You can try it out now! You shouldn’t need any musical training. Just describe what you want to hear (“give me a nice pop melody”), listen to what comes out and keep giving instructions for how to modify it (“add a bass line”).

It does help if you can draw on some music theory or music production knowledge. Among many examples, you can reference scales (“make a melody in E minor”) and the sort of signal processing terms that Switch Angel uses (“add a low-pass filter of 200”). If you know Strudel you can pull up the code at the bottom of the screen to see exactly what’s going on.

I’m a perpetually middling amateur musician, and this represents only a few days of development effort. It comes with definite limitations, some of which I explain further below.

How I used AI: All-in on Claude (4.5 Sonnet)

Of all the AI coding assistants, the current generation of Claude Code (model version 4.5 Sonnet) has probably been getting the most buzz among my friends and around the internet in general. So I resolved to use Claude exclusively and radically while working on what would turn into Vibaldi.

Exploring ideas and architecture: The promise of cheap prototyping fulfilled

I didn’t start out with a clear objective, I only had vague ambitions to generate Strudel code with AI somehow. When I prompted Claude for ideas it came up with uninspiring projects that all felt like discards from a music & AI hackathon. (To be fair, maybe it correctly inferred I’m doing a sort of hackathon.) So I went through several rounds of presenting it with an idea of my own, having it sketch potential architectures and asking it to prototype some of them. Playing the overeager sidekick that it’s designed to be, Claude labelled all of my ideas “fantastic”, “brilliant” or some such.

Claude’s flattery was misplaced; my initial ideas were flawed or unrealistic. E.g., in a failed bid to generatively create music in the style of the baroque composer Vivaldi I tried to extract harmonic content from the score of his seminal work, the Four Seasons (much harder than it sounds, and—I should have known this—harmony alone doesn’t get at the essence of Vivaldi).

If Claude didn’t help much in conceiving ideas or predicting whether they would work out, it excelled at prototyping them. With minimal prompting it stood up working web apps in a Blitz.js stack I’d already established (the wobbly one, see last issue). It correctly integrated Strudel with React on the client side in one shot, including a passable UI with play/pause controls, something that surely would have taken me hours of manual effort.

This really is a game changer. I cycled through a bunch of ideas quickly, validated them in code and got a sense for what they would feel like in a basic UI. Once I settled on an approach to pursue further I still had to put in quite a bit of work. But prototypes or spike solutions have always been a valuable yet expensive technique in software engineering. That their cost now trends towards zero should unlock whole new interesting dynamics in software teams. For one, if prototypes are throw-away code they seem like the ideal low-stakes place for teams to start experimenting with AI agents.

Writing the code: 90% machine, 10% human

Claude Code is Anthropic’s agentic, code-centric version of its flagship model. It took me a while to stop cringing whenever somebody uses the word “agentic” but I’ve come around to appreciate the qualifier. In this context it means Claude as an agent doesn’t just hold a conversation and crank out code, it can invoke and interpret the output of a software engineer’s typical tools, such as package managers, build tools, test frameworks.

I suspect Claude Code’s anecdotally rapid rate of adoption is not only due the quality of its model. From my own hands-on experience, I couldn’t say whether it actually performs better right now than GitHub Copilot and its supposedly lesser models. I think Anthropic’s smart product choices play a significant role. Pretty much all other coding agents (e.g., Copilot, Cursor, Replit) impose a specific IDE-like experience on users while Claude accommodates everyone where they’re already hanging anyway: in the command line.

Claude Code is advertised mainly as a command-line interface, dressed up in ASCII graphics, in a style fallen out of favor lately but reminiscent of vi or Emacs—another smart product choice if you’re courting engineers. In addition, some IDEs have plugins for a more native experience, including VSCode, through which I was personally using the agent for the most part.

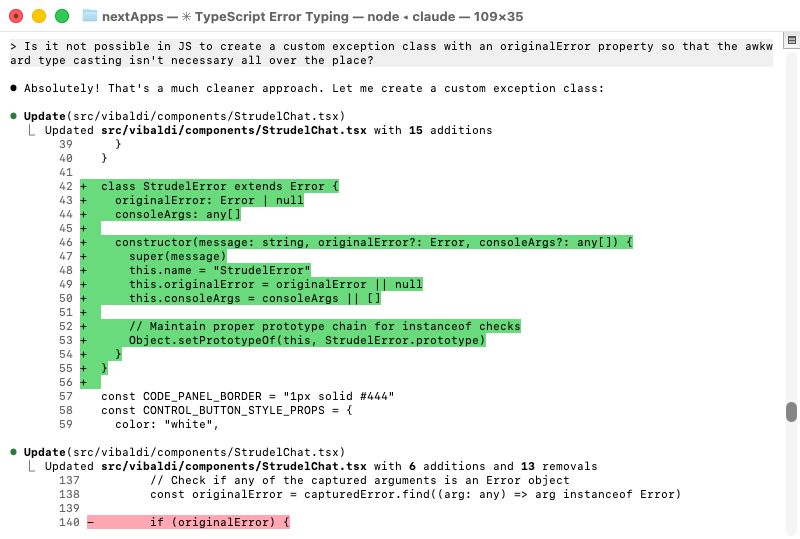

I forced myself to take the backseat and let Claude drive as much of the coding as possible, changes big and small, tests, refactorings, UI elements, styling, all of it. And this worked remarkably well. I would estimate I handwrote less than 10% of Vibaldi, mostly polish and quick small changes on top of Claude’s code. I will put aside the question whether that’s an optimally productive ratio for me personally but committing to the bit convinced me it is viable to go all-in like this right now.

To be clear, I reviewed most of Claude’s output with a senior engineer’s critical eye, often issued follow-up prompts to address shortcomings and occasionally stopped it when it misinterpreted me or was doing something obviously nonsensical.

It’s like having a junior engineer at my command who excels at Googling and stringing together recipes from a handful of Stack Overflow posts but sometimes misses the big picture. I have to ask the same kind of questions I would ask in a typical junior engineer’s code review:

Should this be a separate class/function/component?

Did you consider this other part of the codebase that is already doing something similar?

Is there a library you can bring in to avoid writing this code altogether?

In other words, my decades of grunt work reviewing other people’s code pay off big time. Big, big time. Frankly, the near-daily practice throughout my career made me really good at critically evaluating code. That skill is benefiting me now in more ways than ever. My working thesis is still that, given the current generation of coding agents, experienced engineers have disproportionally more to gain from AI than junior or even mid-level engineers.

Backend: Using the Claude API, agentically

I knew from the start that I wanted to use Claude as a backend via its API, in order to tour even more of its capabilities. This was predicated on Claude being good at emitting Strudel code as well as at understanding music. Both turned out to be true only in a limited sense.

I realised quickly that you can ask Claude to generate Strudel code, out of the box, but the outcome will often be disappointing: it may use made-up Strudel functions, the tempo may be wildly off, layers of sound may be badly matched to each other. I guess the language is too new and too niche to yield a large enough training corpus for a decent model.

Claude itself seemed to recognise this problem. When I first had it build the backend, it wrote an extensive system prompt for itself that tried to capture the syntax and APIs of Strudel. Wait a minute … AIs improving themselves by writing prompts for their own purposes—isn't this what they meant by the singularity??

Well, at the time this is going to press humanity hasn’t gone extinct yet. But this episode maybe illustrates the absurdity of prompt engineering. Less engineering, more cajoling a cat off a tree, it’s the practice of writing prose instructions intended to maximise the quality of a model’s output and/or constrain the type of response it may give (e.g., in the case of Vibaldi we tell the model to respond with Strudel code).

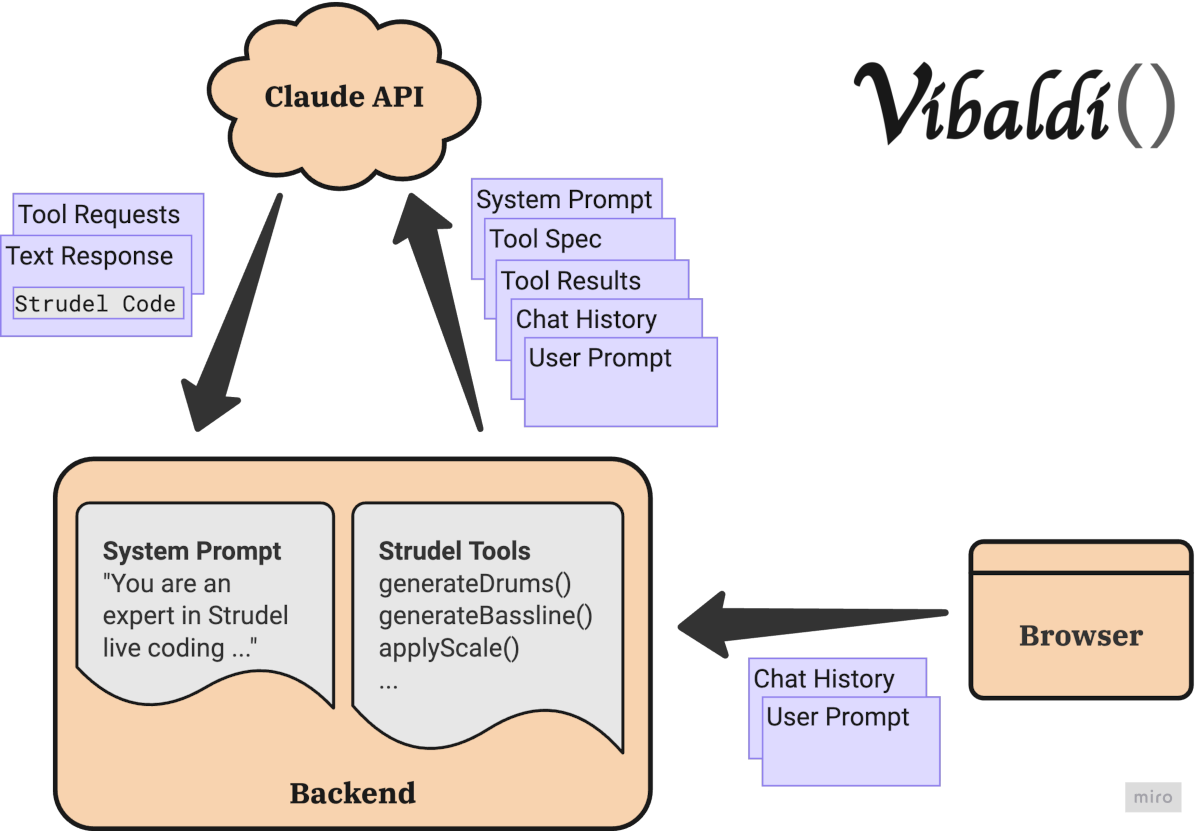

I predict that 5 years from now we will laugh at the clunkiness of then-obsolete prompt engineering. So be it, it’s the main tool we have at our disposal right now to cheaply “customise” a model. The system prompt instructs the model what to do with the user prompt, the actual message entered by the user in the UI. The system and user prompts are sent to the Claude API together. In fact, mimicking Claude’s own statelessness the Vibaldi backend includes the whole chat history with every API request. For simplicity the chat history isn’t stored anywhere but in memory in the browser.

No amount of prompt engineering got me satisfying Strudel output though. I had a breakthrough only when I discovered the Strudel MCP server created by William Zujkowski. He had clearly struggled with similar issues as me and addressed them by manually implementing some key Strudel code transformations, such as for creating drum patterns in specific styles.

I’m not going to get into MCP (Model Context Protocol) here; the Claude API has the related but simpler concept of tools which fit my needs better. Tools exposes local custom code to Claude acting as an agent, such as these controlled Strudel code transformations. If it determines the need to invoke a tool it will request that in its API response, expecting a follow-up message with the result of the tool invocation. This means each user prompt could trigger multiple roundtrips to the Claude API. In this sense, Vibaldi represents an agentic use of Claude.

So taking heavy inspiration from Zujkowski’s MCP server I implemented some tools and started to get better Strudel code as a result. But even if it was screwing up less now, Vibaldi was still often failing to make interesting or pleasant music. I think I was coming up against real limitations of what is possible with Claude alone.

What’s still hard

A recurring section in this newsletter: Given the current state of the art in AI tooling, what remains tedious, time consuming or just plain hard? Or in other words, where are potential opportunities and market gaps?

Judging the sensory experience

Does Claude understand music? This simple question has enough metaphysical and epistemological trap doors for a roundtable of philosophers to dead lock in hot debate. I’m under no illusion that I’m resolving it right now but here’s my current, probably naive thinking: Claude is mainly a Large Language Model; emphasis on language. It knows music theory inside out, naturally, since it has consumed virtually all music theory ever written down, and it can indeed compose a melody in C major, hitting all the right notes, but it can’t say whether that melody would in any way appeal to a human listener. Rather obviously, language is a lossy medium for sensory experience, and that’s true even for the symbolic language of a musical score—or of a piece of Strudel code. Claude can’t make a useful aesthetic judgment about sound based only on a description of sound.

It’s possible that due to these fundamental limitations you cannot really teach music to Claude, not to a point where it comes anywhere close to Switch Angel’s level of skill anyway. It already needed hand holding through the custom Strudel tools I implemented but even then, I would say my short sessions with Vibaldi produce something interesting to listen to only about half the time.

For better results I think it would need to be paired with a specialised model for sound, such as Stable Audio. I briefly looked into it but decided it would be too much effort in the context of this project, mainly because interfacing between these kinds of models and Strudel seemed hard.

Containing the code

When engaging this intensively with a chat-based AI you can’t help but anthromorphise it to a degree. In her excellent piece how to speak to a computer the designer and writer Celine Nguyen reminds us that this effect was observed as far back as the 1960s in the first breakout “AI” chatbot, Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA. On LLMs and intent she writes:

When children are approximately one year old, Wellman notes, they “begin to treat themselves and others as intentional agents and experiencers.” But one of the fascinating things about LLMs is that they aren’t intentional agents [...]. The language model behind ChatGPT, the philosopher of mind David Chalmers remarked, “does not seem to have goals or preferences beyond completing text.” And yet it can accomplish what seems to be goal-directed behavior.

(Read Celine’s whole piece for the useful history of AI as much as her examination of chat interfaces, it’s worth your time.)

I could describe Claude Code as overly enthusiastic and chatty, eager to flatter me and to spend more time with me, but I know it doesn’t have a personality and it indeed doesn’t have goals per se; what it has are conflicting reward functions.

On one hand it must propose optimal solutions to my problems and write optimal code in order for me to want to keep using it, on the other hand it’s incentivised to produce as many tokens as possible in order to squeeze as much money out of me as possible. Your usage of LLMs and by extension what you pay for them is measured in tokens, roughly the number of words that are ingested and emitted by a model as you converse with it.2

Whether conscious product decisions are to blame or not, I think out of the box Claude is currently leaning too much towards more tokens and more code. You can pretty directly observe this in the way it tends to trivially duplicate code and to miss opportunities for 3rd party libraries to cut down on code. It also writes a lot of documentation and redundant comments (you can tell it not to do that).

Engineers react defensively sometimes when I point this out: writing code isn’t the goal of software engineering. Because actually, code is a liability. It costs overwhelmingly more to maintain code than to write it. In an uncanny parallel, this is true whether the maintainer is a human who needs to manage their cognitive load or an AI who needs to conserve tokens.

The goal in software engineering is to write the minimum amount of code that creates the maximum amount of value to users. Powerful socio-technical forces already work to distract most engineering teams from this goal3, and I think coding agents now do too.

I’m largely staying away from the current AI bubble discourse but I will note that those potentially bubbly chip and data center deals are all about compute and thus all about token economics. Will the massive projected expansion of AI infrastructure result in a scarce or abundant token economy? Maybe both at different points in time over the next years, as demand will also increase on an unknown curve. I sort of like the idea that the occasional token drought will incentivise Anthropic to find the verbosity dial and to make Claude’s code more minimalist.

Much discussion of AI coding tools exaggerate either their benefits or their pitfalls. I get it, the hottest takes will get the clicks.

I’m keeping myself grounded and accountable by applying these tools in small real-world projects that I then put out for you, real users, to shake their keyboards at. Hopefully this means I can give a more nuanced perspective on how the craft of software engineering is evolving in an AI-enabled world. Subscribe above and come along for the ride.

—Nik

Pronounced as vibe as in vibing and aldi as in Vivaldi (or Haldimann), glad you asked.

Full transparency on cost: A free Claude plan will not do for anything but the most trivial occasional coding. I subscribed to a Claude Pro plan initially ($17/month) but hit token limits within just a few hours of putting the agent through its paces. I upgraded to the next best plan, Claude Max, with a 5x token limits ($100/month). Sounds pricey but weighing the time savings against my hypothetical hourly rate it’s still actually a steal.

I have a whole book chapter’s worth of thoughts on this topic ready to go, but mainly: engineers—me included—like writing code too much. This may manifest as the well-documented Not Invented Here (NIH) syndrome but it can go as far as manipulating the environment such that problems are more addressable by code than by other means (better design, better user research, better product management etc.).